History of Oil Painting – BOZAR

History of Oil Painting by Romeo Castellucci

Curated by Piersandra Di Matteo

Production BOZAR

Romeo Castellucci presents a new project inspired by the Caravaggism, on the occasion of the exhibition «Théodore van Loon. A Caravaggist painter between Rome and Brussels »

In his sensation dispositifs, as in his theatre work, Romeo Castellucci constantly plots with the history of Western art. He pries rigorously into the roots of the tradition, and seals a pact with the forms of representation so as to dissect the domesticated bonds that tie us to the already known. That is a tactic that allows for the emergence of something unexpected – a behind-the-scenes, perhaps a fissure not foreseen in the image, a defect that calls into question the profound meaning of being a spectator today.

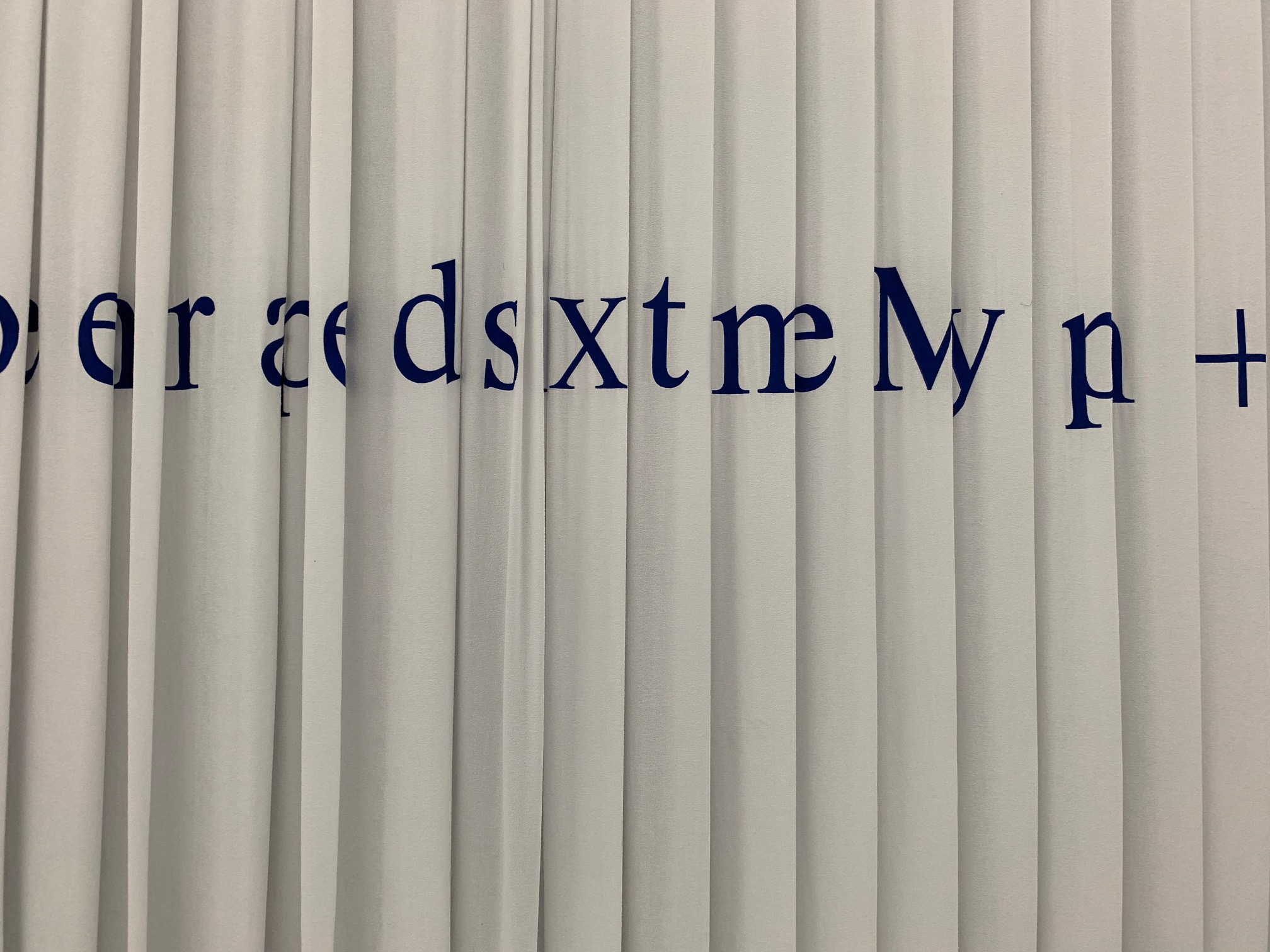

History of Oil Painting, the title of the work presented at BOZAR, reveals at the outset a plane composed of references to the history of art. The installation animates a dramaturgical node that fully anchored to baroque culture. If baroque painting is forever making folds, Castellucci makes the fold the centre of his operation: the walls of an entire room-within-the-room of the exhibition space are lined by white terrycloth drapes that have been carefully organized, fold on fold, fold by fold.

Both form and background, the curve of the fold is caught in its geometric aspect, as a place of refolding, as an artefact that shows the crucial need to hide more than to reveal. The anomaly of the drape, with its shabby and porous fabric, recalls perception to a form of domestic intimacy, a sense of humility. It jostles with the wavelike solemnity of the folds that, arranged as they are in regular intervals, almost outline classic columns. The space created from the weave of the drape intimates a proximity to the body, alluding to the act of washing, of absorbing, of running a sponge over the skin – and, perhaps, with help from the prevailing whiteness, alludes as well to a redemptive washing, a purifying rite.

Here, though, the body is evoked by its absence, through a remainder. The hairs shown in the middle of this room, which resembles a secular chapel, are the fruit of a negotiation, a transaction. They belong to a prostitute who agreed, for a sum of money, to give part of herself to the artist. The biological truth of a piece of the body is revealed in the force of a synecdoche, the part given in place of the whole. The organic offer of the hair, obtained through compensation, is placed on the floor of the art market, hawking its value as a cut object in order to be shown. Like a relic, but without sacred overtones, the lock of hair offers itself to the spectator in the guise of something whose cells hide and contain the genetic key to the anonymous woman who sold it.

This non-symbolic negotiation evokes the centuries-old exchange between the artist and his model. Having established a contract with the prostitute, the model par excellence – a convention that dates back to Praxiteles in Ancient Greece – what Castellucci does, in fact, is stretch a line made tout by the passion for the real inaugurated by Caravaggio, a passion that changes forever the relation between painter and model, marking a point of no return in the history of Western painting. This allusion to art’s ability to embody the truth of a non-idealized subject, a subject marked by the humanity of physical limits, addresses the spectators by name, as if they were looking at their own portrait.

In this triumph of folds – which, suddenly and by association, seems to contain an ethereal world of sacred prostitutes of the temple or Magdalene – the real short-circuiting between the lock of hair and the room is expressed by the stitching technique. The life of this woman-model is condensed in block letters sown onto the terrycloth. The resulting sentence unfolds and hides in the continuous reproduction of the folds. Its folds literally conceal the plot of a discourse, interdicts it (in the etymological sense). This negation seems to say that there is no access to an explainable reality, because it is folded into an infinity of folds. There is no access because it is impossible to explain (impossible, let us say, to unfold) life, because life is irreducible to language. The importance attributed to the linguistic element gives logos precedence over soma and over the flagrant power of its objectivity.

History of Oil Painting is thus a contemplative space not stamped by the subjection to an immaculate whiteness; it is a pure/impure room in which the spectator experiences art insofar as he or she is capable of bearing witness to what falling into a body means.

Piersandra Di Matteo